The 7 Best Engineering Management Books

The 7 engineering management books that every EM should read. Dive deep into each book's key lessons and insights and choose your next read.

The best way to learn about engineering management is not from general ‘leadership’ books, but from actual Engineering Managers.

Today I'll cover the all-time best engineering management books:

- Peopleware: Productive Projects and Teams

- Become an Effective Software Engineering Manager

- An Elegant Puzzle: Systems of Engineering Management

- The Art of Leadership: Small Things, Done Well

- The Manager's Path: A Guide for Tech Leaders Navigating Growth and Change

- Leading Snowflakes: The New Engineering Manager's Handbook

- Extreme Programming Explained: Embrace Change

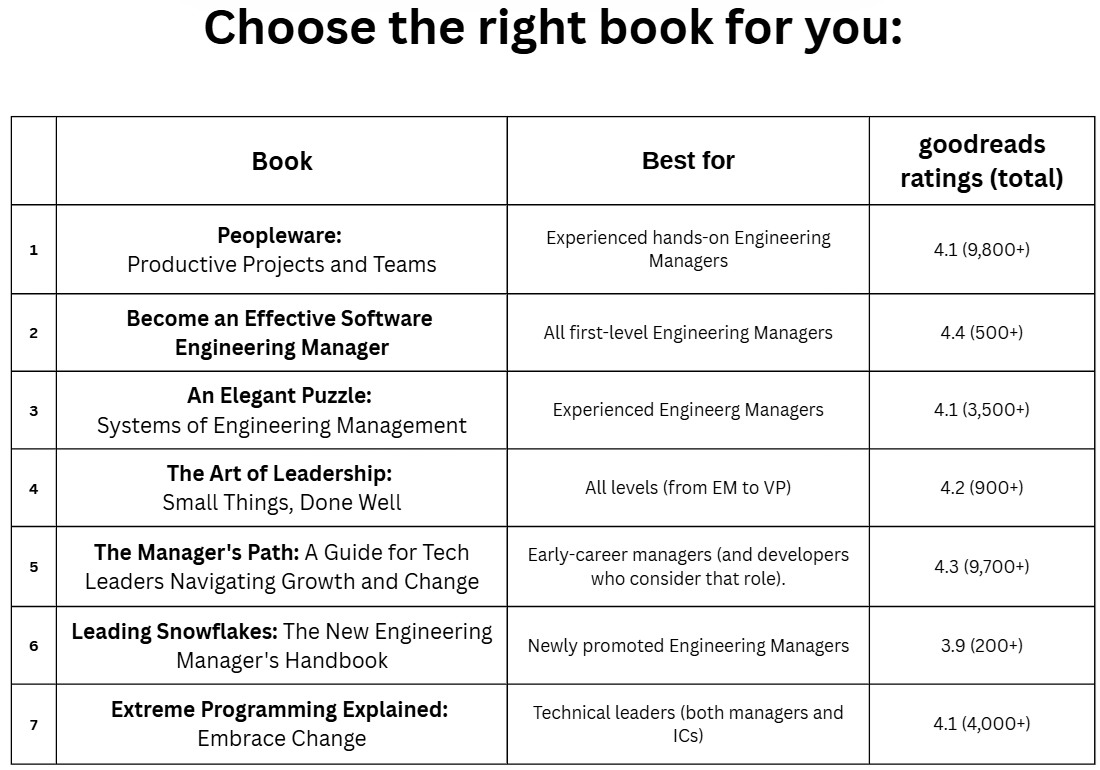

Here's a simple table to help you choose:

For each book, I’ll share some key lessons and which audience it fits best. Most of the article consists of direct quotes from the books, with some minor changes.

Peopleware

By Tom DeMarco and Timothy Lister, 1987, 4.1 on goodreads.

Ideal audience: established managers. Best read when you have some experience.

I've had this one on my reading list for years, thinking that a book published 40 years ago has little to teach. I was so wrong!

My 3 favorite takeaways:

1. Signs of a jelled team

Demarco and Lister coined the term ‘Jelled Team’, which is basically a dream team - and a big chunk of the book is on how to improve the odds it’ll happen to YOUR team.

A jelled team group of people so strongly knit that the whole is greater than the sum of the parts. You know it when you are a part of one.

A few classic signs indicate that you have a jelled team:

- There is a sense of eliteness, team members feel they’re part of something unique. They have a cocky, SWAT Team attitude that may be annoying to people who aren’t part of the group.

- There is low turnover during projects and in the middle of well-defined tasks. The team members aren’t going anywhere till the work is done.

- The final sign of a jelled team is the obvious enjoyment that people take in their work. Jelled teams just feel healthy. The interactions are easy and confident and warm.

You can’t make teams jell. You can hope they will jell; you can cross your fingers; you can act to improve the odds of jelling - but you can’t make it happen. The process is much too fragile to be controlled.

And the book offers some great tips on how to make it happen!

2. A hack for not wasting people’s time

The ultimate management sin is wasting people’s time.

One manager we know from Apple makes a point of releasing at least one person at the start of each meeting. She allows the released person a chance to make a quick statement. She makes it clear that her choice of who gets released is not the person’s relative uselessness, rather it is the importance of the work he or she will be doing instead of sitting in. The savings of a single person released are probably not huge, but the message the release sends is hard to miss.

3. On free electron engineers who define their own job

If your company is fortunate enough to have a self-motivated super-achiever engineer, it’s enough to say, “Define your own job.” Our colleague Steve McMenamin characterizes these workers as “free electrons,” since they have a strong role in choosing their own orbits.

There is a wisdom that everyone needs a firm direction, handed down from above. Most people do - they welcome a clear statement from the boss of just what specific targets are to be met to be considered a success.

Managing the ones who don’t is another matter. The mark of the best manager is an ability to single out the few key spirits who have the proper mix of perspective and maturity and then turn them loose. Such a manager knows that he or she really can’t give direction to these natural free electrons. They have progressed to the point where their own direction is more in the best interest of the organization than any direction that might come down from above.

It’s time to get out of their way.

Become an Effective Software Engineering Manager

By James Stanier, 2020, 4.4 on goodreads.

Ideal audience: First-level Engineering Managers.

My favorite author on Engineering Management - covers EVERYTHING you need to know as a fresh EM. If you have to read one book, get this one. Stanier is still in the trenches, as a Director of Engineering in Shopify, and he writes The Engineering Manager.

Here are my 2 favorite lessons:

Working with Your Manager

You should pull on your manager, not wait for them to push to you. What this means is that it’s up to you to get the best out of the relationship that you have with your manager.

The questions themselves can be straightforward and worked into your conversation:

- “So what’s been on your mind this week?”

- “What’s your biggest worry at the moment?”

- “How are your other staff doing?”

- “What are your peers working on?”

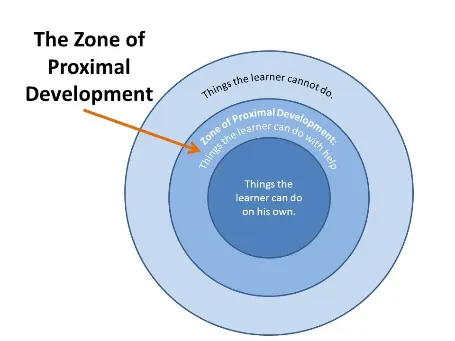

The Zone of Proximal Development

The area where an engineer cannot progress without someone with a higher skill level to assist them. Once the task is understood and completed, they can tackle more difficult tasks, expanding their zone of proximal development.

A key part of games is that the player’s character gains experience as they are playing the game. This experience allows the character to level up and become more powerful. Additionally, characters often earn skill points that they can invest in themselves to get better at particular actions. You often see these skills arranged in a tree, with the achievement of one skill unlocking the ability to achieve the next, building the character’s complete skill set as they progress in the game.

When you spend time with your staff in your one-to-ones, they will talk to you about their desires for their career. Perhaps one day they’d like to be a CTO in their own company, or they’d like to rearchitect the search infrastructure at Google.

As their manager, you can work with them to place these career achievements at the bottom of their own skill tree and then plan out the milestones along the way that they can aim for to make measurable progress - thus pushing the frontier of their zone of proximal development further and further.

Leading Snowflakes

By Oren Ellenbogen, 2013, 3.9 on goodreads

Ideal audience: new managers.

In his short-no-nonsense book (~100 pages), Ellenbogen covers the 9 main lessons he learned along the way from developer to SVP of engineering (with founder/CEO in between). He’s focused on helping just-promoted managers.

Here’s my favorite lesson:

Optimize for business learning

It’s up to us to protect the team from investing in the wrong place. While we may feel this is the CEO’s or the Product Team’s responsibility to make such decisions, it’s our job to make these tradeoffs visible. We cannot afford to bury our heads in the code, hoping things will be fine.

Technical Debt is less scary than getting out of business - optimizing code or scaling up components that may or may not be used is sticking our heads in the sand.

I love to use the famous Pirate Metrics (AARRR) framework for that:

- Acquisition – Figure out how to bring more users to our application.

- Activation – Make sure the user enjoys 1st time experience.

- Retention – Increase repetitive visits to our application.

- Referral – Incentivize your users to bring their friends.

- Revenue – Monetize our users.

If our retention is pretty low and our visitors do not come back to use our application, then we shouldn’t invest money in acquiring more users just yet.

Or, if our activation is poor and almost no one completes the task we believe represents best our value, then investing time in improving retention would probably be a complete waste.

I wrote a dedicated article on the book, where I covered 4 additional lessons (and Oren shared the 2 missing parts he would have added to a 2nd edition):

- “Code Review”ing Your Management Decisions

- Confronting and challenging your teammates

- Building trust with other teams in the organization

- Switching between “Maker” and “Manager” modes

An Elegant Puzzle

Ideal audience: experienced managers (but valuable for beginner EMs too!).

Will Larson is my second most favorite Engineering Management author (after Stanier). He is a CTO at Carta, and writes the Irrational Exuberance blog. His current focus is on more senior leadership/technical strategy, but his earlier works for EMs are amazing.

Here’s my favorite part:

5 Ways engineering managers get stuck

- Only manage down. This often manifests in building something your team wants to build, but which the company and your customers aren’t interested in.

- Only manage up. Some managers focus so much on following their management’s wishes that their team evaporates beneath them.

- Never manage up. Your team’s success and recognition depend significantly on your relationship with your management chain. It’s common for excellent work to go unnoticed because it was never shared upward.

- Don’t spend time building relationships. Your team’s impact depends largely on doing something that other teams or customers want, and getting it shipped out the door. This is extraordinarily hard without a supportive social network within the company.

- Define their role too narrowly. Effective managers tend to become the glue in their team, filling any gaps. Sometimes that means doing things you don’t really want to do, in order to set a good example.

I wrote a dedicated article about that part from the book, where I dove deeper into each mistake and also covered 5 additional ones:

- Forgetting your manager is a human being

- Neglecting Personal Development

- Ignoring destructive behaviors

- Trying to please everyone

- Fighting too hard for your principles

The Manager's Path

By Camille Fournier, 2017, 4.3 on goodreads.

Ideal audience: early-career managers (and developers who consider that role).

The most well-known book on the list, it covers all software engineering roles - from developer to tech lead, EM, CTO, and VP of R&D - and provides valuable insights from Fournier on excelling in each role. It offers more breadth but less depth.

Here’s one insight I loved:

You should demand to be managed

3 key lessons on how to be managed:

- Expect regular one-on-ones, ask for them if needed. Prepare an agenda, and guide your manager to where you need her most.

- Give your manager a break. The manager's job is not to make you happy all the time, but to do what's best for the company and the team. Your relationship with your boss is like any other relationship - the only person you can really change is yourself.

- This said, choose your manager wisely when switching jobs. He may have a huge effect on your career. As often said - people leave managers, not jobs.

The Art of Leadership: Small Things, Done Well

By Michael Lopp, 2020, 4.2 on goodreads.

Ideal audience: all levels.

Lopp is currently a Senior Director of Engineering at Apple, previously VP of Engineering at Slack. He writes the popular Rands in Repose, and manages the biggest engineering leadership community in Slack (30k+), which I really love.

The book is a collection of his best essays, so it’s a bit all over the place, but his writing is the most fun to read. The chapters are divided into 3 parts:

- His time as Manager at Netscape

- Director at Apple (in his first stint there)

- Executive at Slack

Here are 2 parts I loved:

1. A Performance Question

Before you start a ‘performance management’ (or any form of PIP), ask yourself:

“Have you had multiple face-to-face conversations over multiple months with the employee where you have clearly explained and agreed there is a gap in performance, and where you have agreed to specific measurable actions to address that gap?”

-

Multiple conversations. “Rushing it” is a classic mistake in performance management. A manager has one tough conversation, it goes poorly, and they think it’s time for performance management. No. At least three conversations are needed to explain the situation and allow time for questions. Especially for new managers, what you say may not be what’s heard.

-

Face-to-face. Email isn’t enough. Performance feedback needs two-way communication. When delivering tough feedback, you can see how it’s received.

-

Clearly explained. If the issue had an obvious fix, you’d just say, “I asked for XYZ and got ABC. Let’s figure this out.” But when the solution isn’t clear, take time to explain it. Write it down, get feedback, then explain it to your employee. Did it work? Maybe. The key is agreeing to specific actions. If they don’t agree, they won’t act. How do you know? You ask.

2. Delegate Until It Hurts

Your VP gives you a new project. It’s work you’ve done many times. It’d be a slam-dunk if you were solo, but you’re a director, so you hand it to your manager, Julie.

In your 1:1 with Julie, you explain the project—what winning looks like, resourcing, and scheduling. Julie has never done this before, so she asks many questions. You answer fully, and she scribbles down notes, learning. Thirty days into the 90-day project, you hear concerns from the team. You mention discussing it in your next 1:1.

Julie comes prepared. She’s heard the worries and has ideas, but they’re wrong. This is fine. She’s never done it. You discuss a new direction, and she adjusts, asking questions. As the project winds down, the final product is a B. It works, but will need a month of unplanned work before the next release. It’s a B. A voice in your head says, “If it had been me, it’d be an A.”

Shush, little voice. Here’s why a B is credible leadership.

-

First, Julie knew this would stretch her and the team. You showed trust by giving them the project, even though it was beyond their means.

-

Second, when things got bumpy, you didn’t overreact. You sought understanding and coached them through it. More trust.

-

Third, you learned how not to micromanage. You gave initial guidance, answered questions, and let them run with it. When it went sideways, you coached, not punished.

-

Fourth, they did it. The project is done, and they gained valuable experience. How did you do on your first attempt? I likely messed it up in ways you can’t imagine. But in this situation, you’ve increased the odds that the next project by this team and leader has a better chance of being an A.

Delegating familiar work to another is a clear vote of confidence, forming trust within a team. Letting go of the hands-on work is tricky but essential. As a leader, you build yourself by building others.

Extreme Programming Explained

By Kent Beck and Cynthia Andres, 1999, 4.1 on goodreads.

Ideal audience: technical leaders (both managers and ICs).

Extreme programming is “a software development methodology that organizes people to produce higher-quality software more productively”.

In the book, Beck (one of the authors of the Agile Manifesto) presents the values, principles, and practices of XP. Why do we need all 3 types?

"Values and practices are an ocean apart. Values are universal. Ideally, my values as I work are exactly the same as my values in the rest of my life. Practices, however, are intensely situated.

Bridging the gap between values and practices are principles. Principles are domain-specific guidelines for life."

It was written 25 years ago, and 95% of it is still relevant (and unfortunately, rarely implemented in companies). I had many takeaways from the book, but I think that even just reading the values/principles/practices is a great exercise, so here they are:

Values

XP embraces five values to guide development:

- Communication

- Simplicity

- Feedback

- Courage

- Respect

Principles

-

Humanity - People develop software. Part of the challenge of team software development is balancing the needs of the individual with the needs of the team. The team’s needs may meet your own long-term individual goals, so are worth some amount of sacrifice. Always sacrificing your own needs for the team’s doesn’t work.

-

Economics - Make sure what you are doing has business value, meets business goals, and serves business needs.

-

Mutual Benefit - Every activity should benefit all concerned. Extensive internal documentation of software is an example of a practice that violates mutual benefit (you need to suffer for the future person)

-

Self-Similarity - Try copying the structure of one solution into a new context, even at different scales.

-

Improvement - In software development, “perfect” is a verb, not an adjective. There is no perfect process. There is no perfect design. There are no perfect stories. You can, however, perfect your process, your design, and your stories.

-

Diversity - you bring together on the team people with a variety of skills and perspectives.

-

Reflection - Good teams don’t just do their work, they think about how they are working and why they are working. They analyze why they succeeded or failed.

-

Flow - Deploy smaller increments of value ever more frequently.

-

Opportunity - To reach excellence, problems need to turn into opportunities for learning and improvement, not just survival.

-

Redundancy - Defects are addressed in XP by many of the practices: pair programming, continuous integration, sitting together, real customer involvement, and daily deployment, for example.

-

Failure - I coached a team that had several good designers, so good that each of them could come up with two or three ways of solving any given problem. They didn’t want to waste programming time, though, so they wasted talking time instead. Fail instead of talk.

-

Quality - Sacrificing quality is not effective as a means of control. Quality is not a control variable. Projects don’t go faster by accepting lower quality. Quality isn’t a purely economic factor. People need to do work they are proud of. XP chooses scope as the primary means of planning, tracking, and steering projects.

-

Baby Steps - I often ask, “What’s the least you could do that is recognizably in the right direction?”

-

Accepted Responsibility - Responsibility cannot be assigned; it can only be accepted. If someone tries to give you responsibility, only you can decide if you are responsible or if you aren’t. The practices reflect accepted responsibility by, for example, suggesting that whoever signs up to do work also estimates it.

Practices

-

Sit Together - Develop in an open space big enough for the whole team.

-

Whole Team - Include on the team people with all the skills and perspectives necessary for the project to succeed.

-

Informative Workspace - An interested observer should be able to walk into the team space and get a general idea of how the project is going in fifteen seconds.

-

Energized Work - Work only as many hours as you can be productive and only as many hours as you can sustain.

-

Pair Programming - Write all production programs with two people sitting at one machine.

-

Stories - Plan using units of customer-visible functionality. Software development has been steered wrong by the word “requirement”, defined in the dictionary as “something mandatory or obligatory.”And the word “requirement” is just plain wrong.

-

Weekly Cycle - Plan work a week at a time.

-

Quarterly Cycle - Plan work a quarter at a time. Once a quarter reflect on the team, the project, its progress, and its alignment with larger goals.

-

Slack - In any plan, include some minor tasks that can be dropped if you get behind.

-

Ten-Minute Build - Automatically build the whole system and run all of the tests in ten minutes.

-

Continuous Integration - Integrate and test changes after no more than a couple of hours.

-

Test-First Programming - Write a failing automated test before changing any code.

-

Incremental Design - Invest in the design of the system every day, not just once before starting.

The first 13 practices are what Beck calls ‘Primary practices’ - you better start with them. The next 11 are ‘Corollary practices’, which are harder to implement right away.

-

Real Customer Involvement - Make people whose lives and business are affected by your system part of the team. No customer at all, or a “proxy” for a real customer, leads to waste as you develop features that aren’t used,

-

Incremental Deployment - When replacing a legacy system, gradually take over its workload beginning very early in the project.

-

Team Continuity - Keep effective teams together. Value in software is created not just by what people know and do but also by their relationships and what they accomplish together.

-

Shrinking Teams - As a team grows in capability, keep its workload constant but gradually reduce its size. This frees people to form more teams.

-

Root-Cause Analysis - Every time a defect is found after development, eliminate the defect and its cause.

-

Shared Code -Anyone on the team can improve any part of the system at any time.

-

Code and Tests - Maintain only the code and the tests as permanent artifacts. Generate other documents from the code and tests.

-

Single Code Base - There is only one code stream. You can develop in a temporary branch, but never let it live longer than a few hours.

-

Daily Deployment - Put new software into production every night. Any gap between what is on a programmer’s desk and what is in production is a risk.

-

Negotiated Scope Contract - Write contracts for software development that fix time, costs, and quality but call for an ongoing negotiation of the precise scope of the system.

-

Pay-Per-Use - Versus paying per version, or upgrade (a bit obsolete).

FAQ

How can I apply the lessons from these books to real-life management?

Most of the books provide actionable tips that you can apply immediately. Leading Snowflakes specifically, is super practical.

What’s the best way to learn engineering management?

While these books are an excellent starting point, you can't really learn engineering management without practical experience. Apply the concepts you learn, seek feedback, and adapt as you go. Joining communities of engineering managers and mentors can also accelerate your learning (even better - create one inside your own company!)

Are these books still relevant today?

Yes! While Peopleware and Extreme Programming Explained are old, they contain timeless advice and methodologies that remain surprisingly relevant. I was skeptical too.

Which book is best for a new engineering manager?

If you’re just starting your journey as an engineering manager, Become an Effective Software Engineering Manager by James Stanier is my recommendation. It provides comprehensive, practical advice and insights about every area of your job.

Which book is best for an experienced engineering manager?

I would go with An Elegant Puzzle. Larson also wrote 'The Executive Primer' if you are aiming at very senior roles.